Is sugar “physically addictive?” Let’s assess the BS

Q: “Dear Isabel—where do you stand on the concept of physical addiction to white sugar? I’ve seen pictures of how sugar lights up [pleasure centers] in the brain in the same way as cocaine…do you agree that sugar can be physically addictive, and not just emotional? Do you agree that for some of us, sugar can be as bad as heroin?“

Q: “Dear Isabel—where do you stand on the concept of physical addiction to white sugar? I’ve seen pictures of how sugar lights up [pleasure centers] in the brain in the same way as cocaine…do you agree that sugar can be physically addictive, and not just emotional? Do you agree that for some of us, sugar can be as bad as heroin?“

Here’s my response:

You are absolutely right that sugar, sex, music, and basically anything that’s pleasurable lights up “pleasure centers” in the brain—or more specifically, triggers a dopamine response, which is one chemical response triggered by using cocaine.

Additionally, different people may have different chemical responses to different stimuli (e.g. sugar may trigger a more intense dopamine reaction in some, while others may have a more mild response).

That being said,

the clinical definition of “physical addiction” (which is different than “emotional addiction” or simply the feeling of compulsion towards a behavior) is not defined by physical pleasure or the intensity of a dopamine response.

A related, but separate topic altogether, “physical addiction” is defined by physical dependence on a substance—that is, increased physical tolerance for a chemical substance accompanied by the experience of physical withdrawal symptoms when someone stops using.

If you know any heroin addicts they will tell you it is very *physically* painful to come off of…and physical withdrawal from alcohol can literally kill you.

This is not the case with sugar. While some people report feeling temporarily lethargic or lackluster when they initially give up white sugar, physical withdrawal symptoms are mild to nonexistent, and most people report feeling physically better when they eat less refined sugar, rather than the reverse.

Additionally, white sugar breaks down into the same chemical—glucose—as pretty much every other carbohydrate you ingest. The primary difference between white sugar and every other form of carbohydrate you might eat is its refinement (i.e. the stripping away of fiber from the plant foods where sugar is found), not necessarily the chemical itself.

While heavy refinement of carbohydrate-rich foods impacts the speed at which it turns into glucose in our bodies (which can temporarily screw with your hunger signals and may cause health problems over time), glucose is not a foreign chemical to which your body develops “tolerance” the way your body develops tolerance to certain psychoactive chemicals, like opiates or nicotine.

Somewhere in the health and wellness blogosphere the medical community’s very specific definition of “physical addiction” was usurped and distorted by diet and health media professionals—and the results have created a lot of confusion for people struggling with binge eating.

When researchers discovered that eating sugar triggers a dopamine response in the brain—which is pretty unsurprising considering that sugar is delicious—health media and other arms of the diet industry interpreted this to mean that sugar must be “physically addictive” because drugs like cocaine also trigger a dopamine response. They did not note that almost anything that’s pleasurable triggers a dopamine response in the brain as well—pretty sneaky and unethical reporting if you ask me.

Furthermore, these reports implied that “quitting sugar” (aka abstinence programs similar to those used in treatment for drug addiction) must be the answer to “compulsive eating” of sugar… despite the fact that there is no research to backup this claim… and the existence of a dopamine response when engaging in a behavior has nothing to do with gauging physical dependence (aka the criteria of “physical addiction”).

Now, before I discuss why this huge leap in reasoning has caused so many problems for binge eaters, it’s important I address the deeper question underlying your concern…

Why do some people binge on sugar after a single bite, while others can easily moderate without much thought or effort?

In other words—what causes the intense *feeling* of being “addicted to sugar” in some, but not others?

This is the real question on the table and the “pleasure-centers” theory just doesn’t cut it as an answer.

When we dig deeper into the research and look at those folks who feel “out of control” around sugar compared with those who moderate easily without much effort—there is one consistent common variable we see in the “out of control” group:

those who report feeling “addicted” to sugar almost always have a history of feeling restricted or limited around food (and usually sugar in particular).

The more intensely someone restricts their intake of food (or certain foods), the more likely they are to binge eat food in the long run.

Similarly, “emotional eating”—that is, the tendency to turn towards food in moments of emotional duress—is directly correlated with restriction. You can read about this phenomenon (and a slew of related research) in this book.

Given this information, you may see why traditional treatment models for “physical addiction” (which generally involve attempts at abstinence, regulation or control), are likely harmful for those struggling with binge eating—that is, they exacerbate binge eating behaviors in the long run once folks inevitably tire of their restriction attempts.

Thankfully, the “abstinence” model of treatment is not the only one being suggested in the treatment of binge eating. More and more therapists and nutritionists are transitioning to a non-restrictive “anti-diet” model of treatment for binge eating, recognizing the growing body of research linking binge eating with restriction.

While the research is pretty clear that the more someone restricts their food, the more likely they are to binge eat once they “give up” on a restriction attempt, similar research suggests that the cessation of dieting and restriction lessens binge eating in the long term as well.

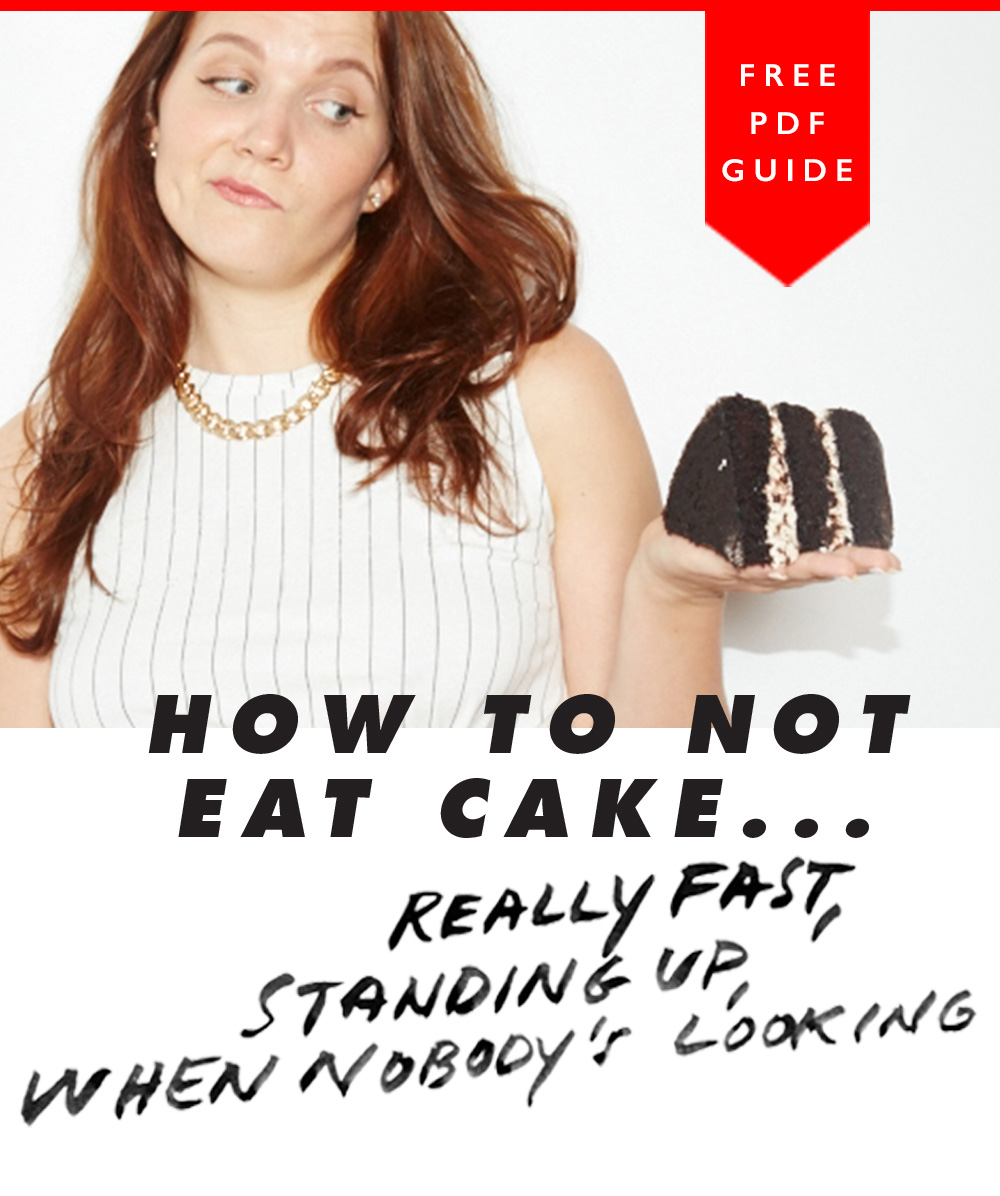

I personally identified as a “sugar addict” for a large portion of my life—I felt completely “out of control” around sugar and would fall into wild binge eating episodes whenever I “let myself” have it.

For years it never occurred to me that my initial restriction of sugar might actually be what was causing these episodes—because I believed humans should be able to control what they eat.

After all, I “choose” what I put in my mouth, right? WRONG.

I didn’t realize that, in fact, humans are animals with animal instincts around food that are quite difficult (if not impossible) to control with will power in the long run.

Trying to control the way we eat can cause dysfunction similar to the dysfunction caused by trying to control sexual or other biological impulses… you might be able to resist for a period of time… but our willpower almost always loses against animal instinct in the long run. The more we try to resist animal instinct, the more likely we are to incur dysfunction long-term.

I eventually discovered the non-diet approach and realized that no amount of therapy or efforts at self-improvement could possibly make restricting sugar “work” in the long run.

Restricting food was the root of the problem, and slowly but surely, as I let go of dieting (both physically and emotionally), the intense psychological pull food had over me—including my highly compulsive and dysfunctional relationship with sugar—started to normalize.

If this approach is new to you, I highly recommend checking out my free video training series (it’s the best intro to some of the most important ideas I’ve learned on my journey towards healing with food and body), or better yet…go deep in the Stop Fighting Food MASTER CLASS—the most comprehensive training I offer on this subject. Click here to check it out.